FEATURED ARTICLE: Mental illness: Still the Cinderella of global health systems research

Dec 6th 2016

Co-authored blog on International Health Policies website hosted by the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium. To view it on the web click here

Mental illness: Still the Cinderella of global health systems research

After attending the Fourth Symposium on Global Health Systems Research (Vancouver, Canada) themed “Resilient and responsive health systems for a changing world” we could not help but search for our lost glass slipper. Influenced by the catastrophic Ebola and Zika outbreaks, this flagship initiative of Health Systems Global (HSG) was immensely successful, if success can be measured by financial investment alone. With support from aid luminaries such as the Rockefeller Foundation, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Wellcome Trust, backed by the World Health Organization, more than 2000 participants attended hundreds of presentations on health system challenges and responses. The Symposium shifted thinking towards resilience and sustainability within health systems and revisited failures and successes of current health system strengthening efforts. Nonetheless there was a glaring oversight: the Symposium programme included little or no focus on mental health and the health system responses towards mental illness as a global health burden.

“No health without mental health”?

Approaching health systems holistically and accepting there cannot be health without mental health, we must consider the importance of mental health in health systems. Mental health is defined as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community”. Health system concepts like resilience and responsiveness – the overarching themes of the Vancouver symposium – are not exclusively macro terms. Within frameworks lie individuals and their dynamic interactions with social and political ecologies. Both health system processes and outcomes – whether resilience, responsiveness, or integration (the usual buzzwords) – are inextricably tied to structure and agency. While resilience and responsiveness focus on the collective, neither individual agency, nor its complex relationship with resilience and responsiveness as collective constructs should be overlooked. It is at this intersection where mental health research is vital. How can we foster resilient and responsive systems without resilient and responsive individuals? For a system to respond to crises (e.g., HIV, Ebola Virus Disease) individual participation in the response is required. However, mental illnesses often renders some incapable of such engagement. Improved population mental health is linked to poverty reduction and improved development outcomes, improved economic health system returns, and improved antiretroviral treatment adherence. Mental health, linked to seven of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), is intertwined with the triple helix of sustainable development – economic, social, and environmental outcomes.

Mental Health: a fundamental but forgotten aspect of health systems research

We can only speculate on the reasons why mental health continues to be the Cinderella of important global health dialogues. Stigma can take on different dimensions, including peril or “otherness”, a condition one can control, concealability, course and stability, and social disruptiveness. These perceptions not only unfold in neighbourhoods and communities, but often in health facilities, amongst health care professionals. Mental health stigma is a profound barrier to care and treatment, and perhaps also to research.

Susan Sontag pointedly remarked, “Any important disease whose causality is murky, and for which treatment is ineffectual, tends to be awash in significance”. The causes, diagnoses, and treatment for the loosely knitted together spectrum of disorders that we know as “mental illness” remains devoid of coherence and consensus. The anti-psychiatry movement during the 1960s and 1970s – while sharpening our focus on the power disparities in psychiatric practice and the negative effects of institutionalisation – arguably also diluted global mistrust in scientific disciplines dedicated to mental illness. With no biological markers, the nebulous nature of mental illness makes it more challenging to explain, measure, research and treat compared to conditions with clear biological markers and those which directly cause death, such as tuberculosis, especially for funders.

In responding to health system shocks, we often myopically focus on survival to the detriment of well-being. Health system shocks (including outbreaks and natural, economic, political disasters) result in those who have experienced death and suffering being forgotten by the health system research and development communities. Ensuring a holistic (and arguably more effective and sustainable) response is an almost impossible ideal to guarantee if health systems are not attuned to the complex social determinants and intricacies of mental illness. Health system researchers must meet this ideal, both as a core function of responsive, resilient and equitable health systems, and by way of moral imperative. It is – from a scientific-moral point of view – less relevant to search for simple answers than to search for difficult ones: where the added value of health systems research lies.

HSR 2018 Liverpool: A call to action

Despite impressive recent strides made to bring mental health in global health dialogues, the omission of mental health at the Symposium highlights disconnect between mental health system discussions, and the more general health system discussion – especially in an era of integrative care. Well-integrated ties among global mental health actors, and policy makers and international governance structures are vital. The almost complete neglect of mental health in the MDGs and its tokenistic inclusion in the SDGs further underwrites the potential contributions that HSG can bring on a global level. Liverpool, home of the Fifth Global Symposium for Health Systems Research and some of the first dedicated mental health facilities by James Currie in the 18thcentury (as well as some local football teams that tend to challenge most fans’ nerves!), provides impetus for prioritising mental illness in global health systems research. We call on the 2018 organisers to include a strong mental health focus in Liverpool focusing on the following broad themes:

- The link between individual and population mental health and health system processes and outcomes (such as strengthening, resilience, responsiveness, functioning)

- Regional and country responses to mental illness

- Building integrated mental health systems in a global climate where mental illness is often disregarded as a serious priority

In its Vancouver statement, resulting from the recent Symposium, HSG concludes with the main objectives of the organisation, namely “improving the science needed to accelerate Universal Health Coverage (UHC); to be more inclusive and innovative towards achieving UHC; and to make health systems more people-centred”. We strongly feel that these ambitious goals are only attainable with sufficient attention for the mental health aspects of health systems. Left aside, we fear that the golden carriages presented at the next ball in Liverpool 2018 might turn out to be simple pumpkins after all…

FEATURED ARTICLE: Time for Action: Shifting the paradigm towards integrated, people-centred health systems

Featured on International Health Policies website hosted by the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium. To view it on the web click here

Time for Action: Shifting the paradigm towards integrated, people-centred health systems

As health system researchers, how do we contribute to a paradigm shift? How do we move the focus from disease specific/fragmented health programs towards integrated, patient-centred health systems, especially given the abundance of disease-specific funding?

At the recent International AIDS Society conference in Vancouver, Canada I lauded the astonishing achievements of expanding HIV testing, treatment and care for millions of people around the globe. I reflected on the initial reluctance to expanding HIV treatment, especially in Africa. Skeptics cited the lack of infrastructure, funding, multisectoral partnerships and human resources as just a few of the insurmountable barriers. Placing 15 million people on HIV treatment was a result of the combined global efforts of activists, researchers, multilateral organisations, donors, pharmaceutical companies and governments, all of whom were tirelessly battling for decades across sectors and geographical and political lines. They were united by the vision of ending the scourge of HIV/AIDS, refusing to accept the skeptics’ objections. Now it is time for health systems and integrated care to move into the spotlight.

During the IAS conference, strengthening health systems and integrated care were only tangentially mentioned – more as an after dinner mint than a main course or even a dessert. For over a decade international researchers warned of the potential of vertical (i.e., disease specific) HIV programs to fragment weak health systems. International agencies and scholars recommended integrating HIV programmes and focusing on strengthening health systems. However, we lack sufficient evidence on the implementation or “how” to create integrated, people-centred health systems. This is especially true in low and middle income countries.

In March 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) released the Interim Report of the Global Strategy on People-Centred and Integrated Health Services. Beginning with a need to focus on health system strengthening and the importance of primary health care and universal health coverage, the report discusses how:

“these approaches encourage and support the development of the health system over vertical programming in an effort to provide people with well-planned, integrated health services required to best respond to their health needs across their lifetime and ensure that necessary services reach the most vulnerable”

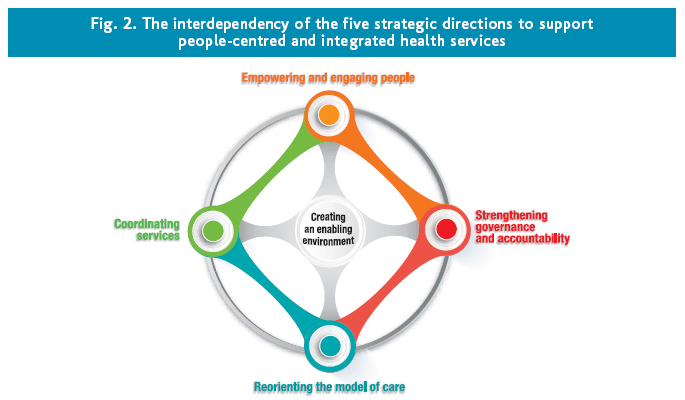

Five interconnected strategic directions are highlighted as seen below:

- Empowering and engaging people

- Strengthening governance and accountability

- Reorientation of the model of care prioritizing primary and community care

- Coordinating services around people including multiple sectors

- Creating an enabling environment

When thinking about “how” to shift the paradigm towards people-centred and integrated health services many challenges exist. These challenges are related to systems, people, organisations and leadership. As summarised in the report, empowering patients, families and communities to become more involved in health care decision making questions the existing medicalised model of health systems (i.e., where medically trained health providers are the sole decision makers). System related challenges include changing organisational, legal, governance and accountability structures within health systems. Disease specific funding and targets within health systems limit intersectoral collaboration. People related challenges include encouraging inter-disciplinarity between professional groups while maintaining patients and communities as equal partners in health care. Organisational- related challenges include the alignment and management of diverse values and goals across regional governing bodies, non-profit organisations and the private sector. Leadership related challenges exist at and within country levels that necessitate models of distributed leadership as people-centred and integrated health services will need to be tailored to local needs.

Many of these challenges are reminiscent of the early dialogue around why a global HIV/AIDS response could not be successful, especially in low and middle income countries. What can we learn from the global HIV response and the related paradigm shift? Researchers, activists, communities, and patients refused to accept that improving access to HIV treatment was impossible, producing evidence and action to bolster this. Likewise, we should not accept that shifting a paradigm towards patient-centred, integrated health systems is impossible. We must recognise the evidence gaps, especially those related to implementation science and challenge our institutions and governments to fill them. We must prioritize health systems research that engages patients and communities to ensure their needs are met. We must develop, test, share and refine metrics of patient and community engagement and integrated service delivery in health systems research. We must bridge across disciplines and sectors to arrive at cost-effective solutions that prioritise patients.

Why is it no longer acceptable to die at the hands of a virus like HIV but is it still considered acceptable to die due to modifiable health system factors? The time to change is now. Our health systems can and should meet the needs of patients and communities. So let’s get started.

VIDEO: Groundbreaking BC Research into HIV-AIDS

Featured on Global News. July 21 2015To view it on the web click here

INTERVIEW: One stop health care model transforms HIV treatment in South Africa

Press Release on the research with an interview. Click here. One stop health care model transforms HIV treatment in South Africa

A rural township in Free State. Credit: Angeli Rawat

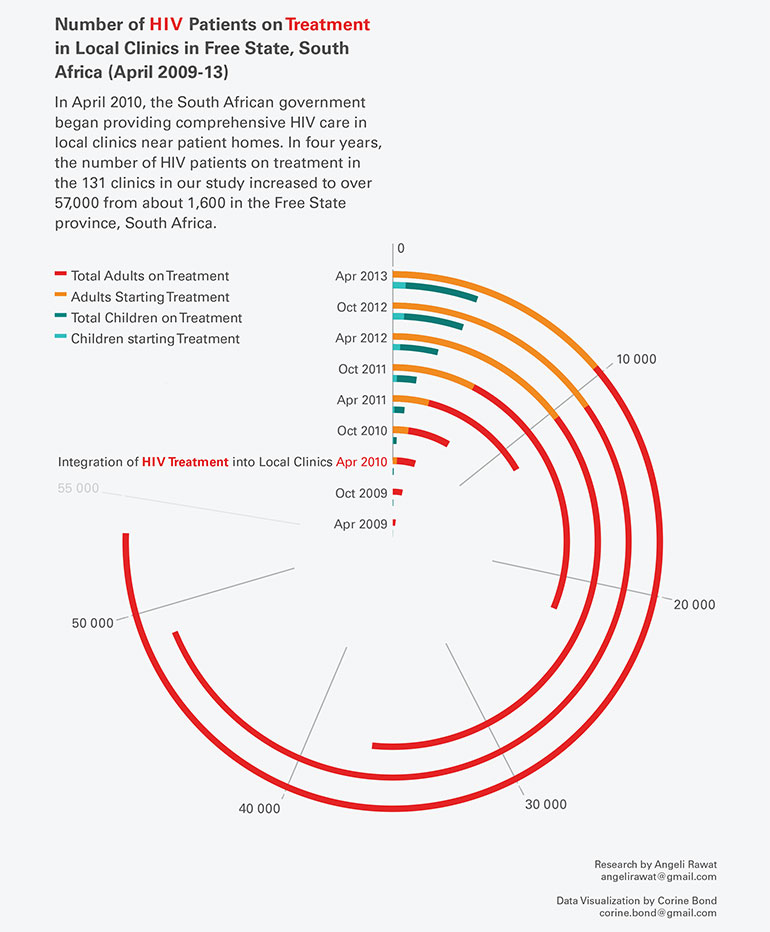

Providing HIV care at local health clinics in South Africa has led to a massive increase in the number of people there receiving vital HIV treatment, according to UBC research.

Indeed, the number of patients receiving HIV therapy in these clinics soared to more than 57,000 from about 1,600 over the four-year period – an increase of nearly 3,500 per cent. Almost 44,000 of these patients had never been on HIV treatment before.

That’s a notable outcome, given that South Africa has among the highest rates of people living with HIV in the world – nearly 10 per cent of the population. The country also has some of the highest HIV and tuberculosis co-infection rates.

In addition, South Africa has the largest HIV-treatment program in the world. In April 2010, a national policy was implemented that stated that all South Africans should be able to access comprehensive HIV treatment and care at the clinic nearest their homes.

Angeli Rawat, a Liu Scholar and recent PhD recipient at UBC’s School of Population and Public Health, has researched the impact of this integrated model. Her dissertation examined the implementation of HIV care at 131 primary health care (PHC) clinics in South Africa’s Free State province, representing a population of 1.5 million, between 2009-2013.

Rawat presents her research at the IAS 2015 conference in Vancouver, July 19-22. Here, she discusses some of the highlights of her work.

Your research in South Africa found that bringing HIV care closer to people’s communities can have a huge impact. Why?

Health systems are like woven fabrics – when you pull on one thread, the rest of the fabric adjusts. I looked at how a health system responds when you bring HIV care down to the level of the local clinic.

Before this integration, HIV patients had to leave their communities and travel to many facilities, many times. Forty per cent of those who needed HIV treatment weren’t getting it, especially the most economically disadvantaged. Patients don’t have money to pay for transportation and the time to travel far. Many passed away while waiting for treatment.

Patients now have access to comprehensive care at their local PHC clinics. Integration also improved HIV screening and the treatment process for HIV-positive mothers and babies.

In addition, integration highlighted the importance of primary health care. Patients were counselled on potential side effects of their treatment, and learned about their medications. They had treatment buddies and support systems. It puts the patient back into the centre of the health care equation.

There are many advantages for health care workers. Integration improved their skills, confidence and morale. Many nurses said to me, “When I see a patient who was so sick from HIV that he had to be carried into the clinic in a wheelbarrow – and then I see him get better on HIV treatment and return back to work in a few weeks – that makes me feel good. I did that!”

Number of HIV patients on treatment in local clinics in Free State, South Africa (Click image to enlarge)

What was the impact on the stigma surrounding HIV?

I believe the advantages of integrated care have had an immense impact in terms of decreasing HIV-related stigma. This means HIV patients are treated the same as all other patients – no separate queues, specific consultation rooms or identifiers on files. Patients and health care workers told me that this “normalized” HIV because now it was treated the same way as other conditions, and you weren’t sent far away to a “special” clinic.

Another advantage is that people in a waiting area would strike up conversations about HIV. When HIV patients were seen as productive and healthy members of the community, this shattered images of HIV being a death sentence.

Now that care was nearby, patients could bring a partner or friend to support them. This empowered and unified communities to fight stigma and educate each other.

The massive increase in patients receiving antiretroviral therapy is astounding. How could the clinics handle such a dramatic increase?

You’re right – the increase is phenomenal. And the fact that the provision of primary health care services wasn’t overwhelmed was great.

Many HIV-positive patients were coming to the PHC clinics for all their other health needs. Some health care workers reported that there was not a massive increase in patient numbers – these were patients who lived in the area who should have been coming to the clinics in the first place.

There were also increased efficiencies. Health care workers were no longer spending time on referrals, and protocols and services were streamlined. Our participants felt that integration promoted teamwork. They could treat patients holistically and were able to shift some of their tasks to other care providers, such as community health workers.

The next challenge is really about maintaining high-quality care for all patients within these systems, taking care of the health workers and keeping patients engaged in HIV care across their lifetime – especially as HIV and aging foster new issues.

IAS 2015 is the world’s largest scientific conference on HIV and AIDS. This year’s event is organized by the IAS in partnership with the UBC Division of AIDS and runs from July 19-22.

VIDEO: A preview of Angeli Rawat’s research on HIV treatment expansion in Free State, South Africa.

|

A good blog always comes-up with new and exciting information and while reading I have feel that this blog is really have all those quality that qualify a blog to be a one.

ReplyDeletestar health optima vs comprehensive